Legal and political background

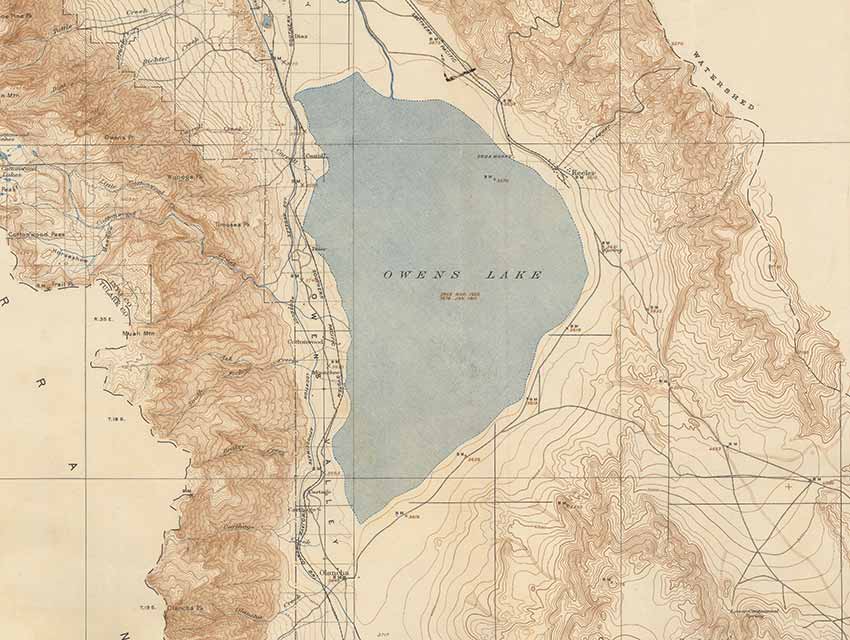

In 1913 Los Angeles diverted Owens River from its channel leading to Owens Lake, into an aqueduct leading to Los Angeles. Thus began the drying of Owens Lake. By 1924 the drying was complete and the dried lakebed was becoming a major source of air pollution in the form of blowing dust. By the mid 1990’s, it had become the largest single source of PM-10 in the United States.

California lawmakers established Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District 1974 to enforce federal, state and local air quality regulations and insure air quality standards are met. In 1983, the California legislature passed SB 270, codified as section 42316 of the California Health and Safety Code, which gave GBUAPCD authority to undertake reasonable measures to mitigate dust and recover costs from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP).

In 1998, under intense political pressure, LADWP and GBUAPCD signed a State Implementation Plan (SIP) setting forth how LADWP would mitigate dust. Another SIP, amendments to the SIPs and legal challenges by LADWP followed. State courts consistently rejected LADWP’s various challenges and upheld GBUAPCD’s enforcement orders.

By 2012 LADWP had implemented dust mitigation measures on 45 square miles of the lakebed and air pollution had been reduced by over 90%. However, GBUAPCD’s data had demonstrated that a 99% reduction in pollution was necessary to meet federal air quality standards, hence in June 2012 GBUAPCD ordered LADWP to mitigate dust in about 3 more square miles of lakebed.

In June 2012, DWP declared it was “done” at Owens Lake and would not implement further mitigation measures, meaning it would not comply with GBUAPCD’s order of June 2012 to mitigate dust in about 3 more square miles of lakebed. In October 2012 LADWP then filed a lawsuit in Federal court seeking, among other things, to invalidate all existing agreements, declare California Public Health and Safety Code 42316 “unenforceable” and have GBUAPCD regulator Ted Schade removed from any future dealings with LADWP on the grounds that he is “biased.” This litigation is ongoing as of April 2013.

GBUAPCD has currently approved three methods for dust mitigation: shallow flooding, managed vegetation, and spreading gravel. LADWP chooses which dust mitigation method it will use for each portion of the lakebed. LADWP has chosen the shallow flooding method for most of the 45 square miles on which it has implemented dust mitgation measures.

In choosing this method, DWP inadvertently re-created a variety of habitats for water-birds, a fact quickly discovered by water-birds and bird-watchers alike. Because the bird habitat was created inadvertently, there was a concern among environmental groups that DWP might switch to less water-consumptive methods of dust mitigation in the future, thereby destroying the valuable and extensive habitat. The Eastern Sierra Audubon Society took the lead in seeking a commitment from LADWP to protect the bird habitat.

Master Plan negotiations

Due in part to longstanding efforts by the Eastern Sierra Audubon Society, LADWP “convened a broad collaborative process to develop a ‘Master Plan’ for the Owens Lakebed” in March 2010. Almost every county, state, federal, and tribal entity in Owens Valley, along with environmental groups and several individuals joined the “Owens Lake Planning Committee.” The Center for Collaborative Policy provided facilitation.

A complicated organizational structure developed, consisting of a steering committee, an agency forum, a stakeholder forum, subcommittees, and work groups. A work plan, and a website also appeared. The objective was to identify “broadly supported goals” regarding management of the lake. The planning process focused on “dust mitigation, habitat and wildlife, water efficiency methods, and potential renewable energy development.” It included detailed rules for consensus-based decision-making, and according to one participant, much time was spent “singing Kumbaya.”

A Draft Master Plan was released in December 2011. Environmental groups were shocked to find the draft contained contentious material to which they had never agreed. Planning Committee members and the public submitted comments, through early February, 2012, but the comments were never addressed. Meanwhile, LADWP ceased holding Planning Committee meetings and, instead, initiated media attacks on GBUAPCD for “demanding” DWP “waste water” to mitigate dust on Owens Lake.

In October 2012 LADWP sued GBAUPCD and other agencies, invoking Master Plan negotiations in the justification for its lawsuit. After LADWP filed its lawsuit, continued participation by Inyo County and environmental groups was publicly criticized, and local environmental groups were compared in the LA Times to the cowardly townspeople in the classic Western, “High Noon.”

After a hiatus of about eight months, the Planning Committee finally met on Jan 28, 2013. At this meeting LADWP distributed a list of “must have” items for the Master Plan. The meeting facilitator then encouraged other Planning Committee members to identity their own “bottom lines” but without “drawing lines in the sand.” The Owens Valley Committee’s response is here.

On March 26, 2013, two days before OVC released its response to LADWP’s must have list, LADWP wrote a letter to Planning Committee members explaining it had decided to develop an Owens Lake master plan unilaterally. The Master Plan negotiating process was thus terminated by LADWP before there was any formal agreement on a Master Plan.

Discussion

Although Master Plan negotiations were aborted by LADWP, they can be credited with a potentially important accomplishment. The Habitat Subcommittee developed the concept of a “habitat suitability index” as a means to quantify the habitat value of a given dust mitigation technique for different guilds of water fowl. The subcommittee then applied this approach to the lakebed and developed a “fuzzy map” which reportedly showed that even if DWP switched to less water-consumptive dust mitigation techniques, it was theoretically possible that habitat value (as measured by the habitat suitability index) could be maintained.

Both LADWP and the California State Lands Commission (SLC) embraced the notion of using the habitat suitabiltiy index as a way to maintain public trust wildlife habitat values while using less water for dust mitigation. As the owner of most of the lakebed on which LADWP must mitigate dust, SLC has veto power over LADWP’s dust mitigation efforts. If LADWP chooses to ignore the habitat suitability index values in future management decisions, SLC will, presumably, object and insist the values be maintained.

There were numerous comments on the Draft Master Plan, but four aspects of the draft were the subject of particular public criticism: 1) language laying the groundwork for new groundwater pumping; 2) omission of any language obligating LADWP to leave “saved” water (i.e. water no longer needed for dust mitigation) in Owens Valley; 3) language committing Planning Committee members to advocate temporary suspension of air quality standards to facilitate LADWP efforts to change to less water-consumptive dust mitigation techniques; and 4) use of the word “conservation” as a euphemism to refer to LADWP’s efforts to use less water on Owens Lake in order to provide more water for consumptive use in LA.

When LADWP failed to address comments and began using the negotiations in its attacks on GBUAPCD, it was argued that negotiating partners were being used as pawns in LADWP’s media and legal campaign and negotiations should be ended. Continued participation by environmental groups and Inyo County was also criticized as pointless, because Master Plan negotiations were voluntary, hence there was no leverage to force LADWP to give ground on the crucial issues of LADWP’s desire to include new groundwater pumping in the plan, and its refusal to commit to use any “saved” water in Owens Valley.

Either Master Plan negotiations would give LADWP what it wanted, or LADWP would not agree to a Master Plan. Finally, there was nothing to gain by continued participation of environmental groups because LADWP and SLC had already agreed on the use of habitat suitability index to protect bird habitat, hence the principal environmental benefit had already been realized.

The negotiations are a striking example of LADWP’s use of the “divide and conquer” strategy. For years LADWP has failed to meet its obligations under the Inyo-LA-Long Term Water Agreement to supply water to irrigators, and has blamed irrigation water shortages on LADWP’s obligation to supply water to environmental mitigation projects such as the Lower Owens River Project. In other words, LADWP has pitted local ranching interests against local environmental interests. In Master Plan negotiations LADWP divided Owens Valley groups in two new ways.

First, LADWP broke new ground by successfully pitting local environmental groups (along with itself) against GBUAPCD, the agency responsible for the most effective environmental mitigation project in Owens Valley history. LADWP claimed in its media campaign that local agencies and environmental groups were cooperating with LADWP in Master Plan negotiations, while GBUAPCD was not.

Local environmental groups acquiesced to this mis-representation (with the exception of the Owens Valley Committee, which belatedly objected). This acquiescence led to division within the local environmental community over whether to continue the negotiations: a second success for “divide and conquer!”

Aftermath

Now that negotiations have fallen apart, LADWP is seeking endorsement from Inyo County Supervisors for the “Owens Lake Master Project” it is developing unilaterally. Given that the project will undoubtedly call for new groundwater pumping and will not call for keeping any “saved” water in Owens Valley, it is not clear why Inyo County Supervisors would have any incentive to endorse it.

LADWP is also seeking to persuade members of the Habitat Subcommittee (of the now-defunct Owens Lake Planning Committee) to continue to meet in order to help LADWP define “sustainable” levels of groundwater pumping in its new wellfield near Owens Lake. Given that: 1) LADWP has already decided it will pump from about 9,000 – 15,000 acre-feet of water annually; 2) LADWP’s consultants have determined that such pumping will produce impacts already found to be unacceptable to the Inyo County public; and 3) LADWP has a history of using the existence of talks with environmental groups (even when no agreement has been reached) to try to greenwash its image, it is not clear why any members of the Habitat Subcommittee (other than LADWP) would wish to meet.