Historically, Owens Lake was one of the most important stopover sites for migrating waterfowl and shorebirds in the western United States for thousands of years. Joseph Grinnell, visiting the lake in 1917 from the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology in Berkeley, reported, “ Great numbers of water birds are in sight along the lake shore–avocets, phalaropes, ducks.

Large flocks of shorebirds in flight over the water in the distance, wheeling about show in mass, now silvery now dark, against the gray-blue of the water. There must be literally thousands of birds within sight of this one spot. En route around the south end of Owens Lake to Olancha saw water birds almost continuously.”

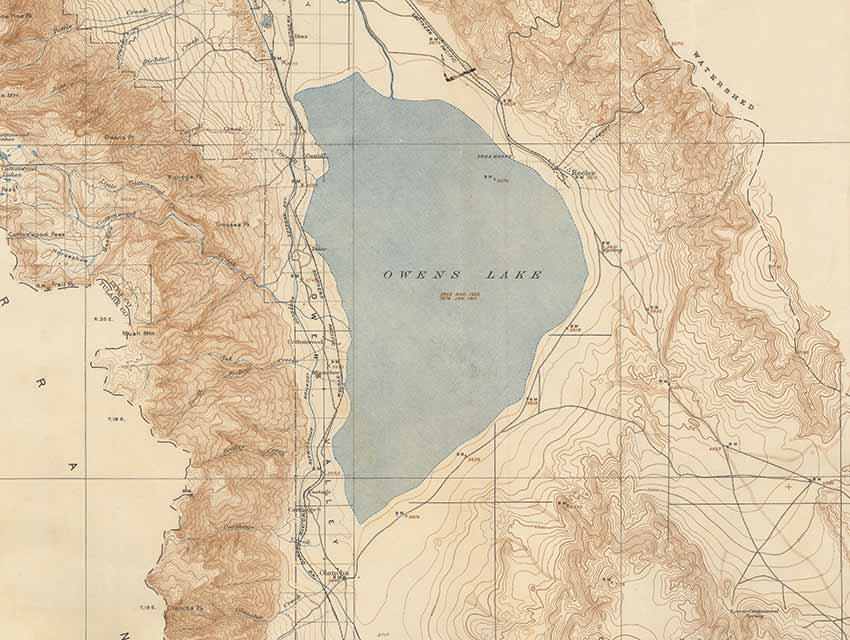

Although water once flowed into the lake from the Owens River, the lake eventually became “possibly the greatest or most intense human-disturbed dust source on earth” (Todd Hinkley, reporting for the U.S. Geological Survey in the mid-1990s) after the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) diverted the lower Owens River to the Los Angeles aqueduct in 1913.

Although a chain of wetlands lining the lake’s shores with water from springs and artesian wells kept some of the lake alive, windblown dust from the lakebed–a toxic cocktail of arsenic, cadmium, nickel, and sulfates–has been found across the West.

A 1999 Memorandum of Agreement with GBUAPCD, a 2003 State Implementation Plan, and an additional 2006 agreement between GBUAPCD and LADWP require Los Angeles to implement dust control measures on the lakebed in order to meet federal air quality standards, a goal for which the most recent deadline was 2010.

Owens Lake is a nationally significant Important Bird Area (IBA) as designated by the National Audubon Society. The lake was so designated due to the thousands of shorebirds that migrate through each fall and spring between the Arctic and Central and South America and also because of the large numbers of snowy plovers that nest there. In addition, several thousand snow geese and ducks winter at the lake.

In spring, thousands of migrating shorebirds move north from wintering areas as far south as Argentina (Patagonia) and Tierra del Fuego. These masses of birds migrate through North America to breed in the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada as well as the high Arctic along the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean. Along the routes, migrants stop at rich feeding sites such as coastal wetlands and estuaries as well as inland lakes in the Great Basin such as Mono Lake, Great Salt Lake, and–once again–Owens Lake.

Geologic records show that they have stopped at Owens Lake for at least 800,000 years. Feeding stopovers are few and far between, even for these marathoner bird species. Necessary fat reserves must be put on to enable the migrants to reach the next stop, which may be hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Birds must arrive at breeding grounds to the north by the middle of May.

As of 2013, the Los Angeles Owens Lake Dust Control Project stretches across about 45 of the Lake’s 100 square miles. Roughly 3.5 square miles are covered with native salt grass grown on a drip system. The remaining 41.5 square miles are covered with ponded water or are sheet flooded. These water-based dust control methods have re-created an Owens Lake food web for birds.

Since the initiation of shallow flooding dust control measures in 2001, the lake has become a significant migratory stopover once again. During an April 2008 “Big Day” bird counting event, 49 volunteer birders observed 112 species and a total of at least 46,650 birds–including black-bellied and snowy plovers, western and least sandpipers, long-billed curlews, and thousands of California gulls, American avocets, eared grebes, small sandpipers, and ducks, respectively–at the Owens Lake.

During a smaller “Big Day” event in August 2008, 13 volunteers recorded 42,754 birds of 71 different species patronizing dust control areas, including peregrine falcons, hundreds of white-faced ibis and black-necked stilts, and thousands of American avocets, northern shovelers, western and least sandpipers, California gulls, and Wilson’s and red-necked phalaropes.

In fall 2008, the last phase of the dust control project began, to be completed in 2010. More than nine square miles of additional ponds and sheet flooding were built. LADWP is also scheduled to complete a long-term habitat management plan for the entire dust control project.

Although to date Los Angeles has met most of its dust control requirements with shallow flooding for dust control measures, the agency could, in theory, greatly reduce shallow flooding on the lakebed in favor of other approved dust control methods–vegetation or gravel–as long as emissions from the lakebed comply with federal air quality standards.

Look for Eastern Sierra Audubon Society field trips to Owens Lake or contact Mike Prather at 760-876-5807 or at [email protected]

On the web, photos of the Owens Lake are on display at David Maisel’s Lake Project slide show at Grist Magazine, Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District’s Owens Lake Dust Cam site, and the Library of Congress (search for “Owens Lake” to see a 1911 panoramic shot of the lake with water in it). See also: a checklist of the birds of Owens Lake.